A new feature from Ring, owned by Amazon, has drawn criticism from privacy advocates and lawmakers after a Super Bowl advertisement highlighted the company’s expanding neighborhood surveillance capabilities.

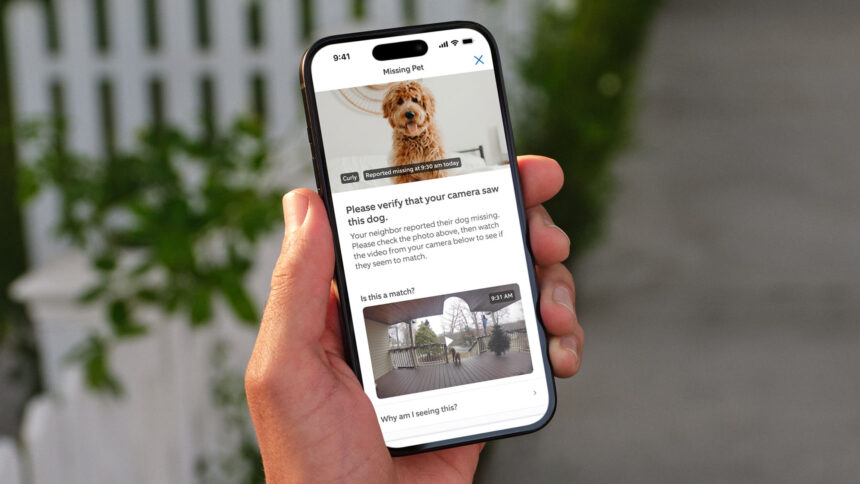

The 30-second commercial showcased Ring cameras working together across a community to help locate a missing dog using the company’s new Search Party feature. While intended as a feel-good example of technology helping neighbours, the campaign has instead reignited concerns about the broader implications of AI-powered surveillance networks.

Concerns over potential human tracking

Critics argue that the same artificial intelligence used to identify animals could eventually be adapted to track people. The concerns come amid Ring’s recent introduction of a facial recognition feature and its ongoing efforts to expand AI capabilities across its camera ecosystem.

Privacy expert Chris Gilliard described the ad as an attempt to “put a cuddly face” on what he called a growing network of residential surveillance. U.S. Senator Ed Markey also criticised the initiative on social media, warning that the technology could contribute to mass surveillance rather than simply helping pet owners.

How Search Party works

The feature is enabled by default for outdoor cameras subscribed to Ring’s paid plan. When a pet owner uploads a photo to the Neighbors app, Ring’s cloud-based AI scans nearby camera footage for matches.

If a potential match is detected, the camera owner receives a notification and can choose whether to share the video or contact the pet’s owner. According to Ring, the system currently identifies only dogs and does not process human biometric data.

The company also emphasized that its Familiar Faces facial recognition feature operates separately at the individual account level and is opt-in.

Law enforcement ties raise additional scrutiny

Much of the backlash centers on Ring’s partnerships with public safety technology providers, including Flock Safety, which supplies automated license plate readers and other monitoring tools used by law enforcement.

Advocates worry that linking a vast residential camera network with organizations that work closely with police could expand government access to neighborhood footage. Ring said its integration with Flock is not yet active and that any future implementation would be limited to local public safety use.

The company maintains that law enforcement cannot access camera footage directly. Instead, agencies must request video through a feature called Community Requests, and users can choose whether to share it.

Company denies surveillance intent

Ring spokesperson Emma Daniels said the Search Party system “is not capable of processing human biometrics” and stressed that the company has no partnerships with federal agencies such as immigration enforcement. She added that Search Party and facial recognition operate under different safeguards and that the company has no plans to develop people-tracking capabilities.

“These are not tools for mass surveillance,” Daniels said, noting that the company aims to provide transparency and user control.

Trust remains the central issue

Despite those assurances, privacy groups argue that the rapid expansion of AI-enabled camera networks raises long-term concerns. Critics note that technologies built for limited purposes have historically been repurposed for broader monitoring.

As Ring continues to promote AI as a tool for crime prevention and community safety, the debate is shifting beyond individual features to a broader question: how much trust users are willing to place in companies operating large-scale surveillance infrastructure.

The controversy highlights the growing tension between convenience, security and privacy as consumer technology becomes more deeply integrated into everyday neighborhood life.